Crime

Handcuffs, Queensland Police Museum. Anastasia Dukova

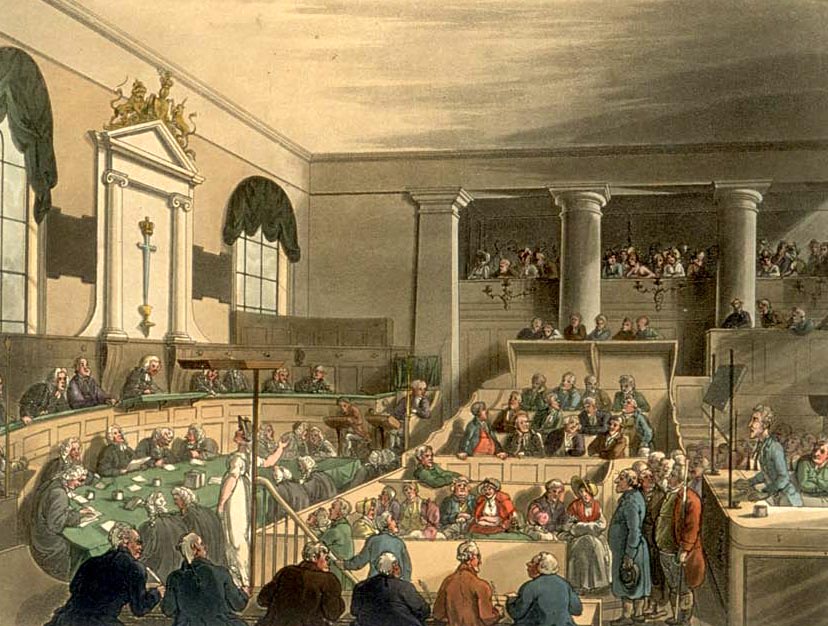

George Cruikshank, The Drunkard's Children (c. 1847) - showing the interior of the Old Bailey with the drunkard's children in the dock for robbery under the influence of alcohol. Collage, record number 26626. © London Metropolitan Archives.

Moreton Bay, Australia

Consistently, ‘drunkenness’ or ‘drunk and disorderly’ are amongst the most numerous offences in police statistics across the urban forces in the colonies and England, and Ireland, this included the Moreton Bay settlement. Therefore, a significant number of drunk and disorderly arrests is not a unique or isolated incident. Having said that, the handful of night and day Brisbane ordinary constables were kept busy indeed, as there was a total of 615 misdemeanours prosecuted in that year. Below is the breakdown of the summary offences disposed of by the Police Magistrate for 1859 (Pugh's Almanac 1859, p. 41):

Common Assaults 40

Embezzlement 20

Masters and Servants Act 78

Rogues and Vagabonds 71

Drunk and disorderly 337

Indecent exposure 4

Late 18th to early 20th centuries, Great Britain

The vast majority of crimes prosecuted between 1780 and 1925 were property offences.

Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, society tended to follow a harm-reduction model, where crime should be prevented by paid police officers. In the eighteenth century through to around the start of World War I, the victim was the critical actor in defining crime and taking action against a criminal. In the eighteenth century - as described in more detail in the Policing pages - victims of crime were aided by local parish officers, constables, and private prosecution agencies, or could pay an annual subscription to have a "detective" track down their stolen property, or prosecute them in court.

So, the numbers and types of crimes that were prosecuted relied on an active victim who was determined to take the cases to court. Employers could sack workers who stole their workplace materials. Victims of assault could use physical retribution themselves; violent husbands could be subject to "Rough Music" (community sanctions) in their neighbourhood.

The crimes that did not make it into court tell us as much as the crimes that did, but it is the latter which the evidence forces us to focus on. It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the government published annual crime statistics. Although these were deeply flawed, it is possible to see how crime (or prosecution) trends were presented, and determine why the Victorian State and the general public reacted to apparent outbreaks of crime at particular times.

Moral panics

The years between the 1880s and 1930 has been characterized as the era of the “Policeman State” by Vic Gatrell (1992). Over this time, the police slowly grew to exert a powerful influence over recorded crime through the centrality of their role in the detection and prosecution process. They effectively replaced the victim in court, taking the main role as both the apprehenders and prosecutors of criminality. This affected prosecutions for violence, especially, and they fell dramatically. If violent crime did appear to be falling, it did not prevent the public (or the newspapers) reporting on a number of crime-related panics in the mid- to late nineteenth century.

Total number of Prosecutions in England and Wales, 1856-1940. © Digital Panopticon.

The nineteenth century sporadically experienced periods of heightened anxiety, particularly about violent crime. Following the end of convict transportation in the mid 1850s, insecurities increased as convicts who would have completed their sentences on Australian soil (and then stay there) were released from British prisons. Concern grew that ex-prisoners would be free to reoffend on the streets of the capital. When some of these "ticket-of-leave" men were suspected of committing violent crimes in the 1860s, the popular press ensured that a relatively small increase in violent crime was widely reported. It grew into a - what we now would commonly term - "moral panic" about violent ex-offenders, epitomised in a high-profile incident of "garrotting" (the strangulation of mugging victims with a knotted rope).

The most well-known panic centred around the spate of murders in Whitechapel in 1888. As the coverage of garrotting and Jack the Ripper shows, our knowledge of crime in this period is mediated by the sources we have available to examine the subject.

For the eighteenth century, we can learn something about more serious offending through reports of trials in broadsides and published trial reports, notably the Old Bailey Proceedings. In addition, this website has records of minor crimes, in the Bridewell House of Correction Prisoners 1780-1795 and the Middlesex House of Detention Calendars, 1836-1889.

Digital Panopticon

This abridged feature is reproduced with thanks and acknowledgements from Digital Panopticon, a collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool, Sheffield, Tasmania, Oxford and Sussex, with funding from the AHRC.

Further Information:

Gatrell, V. A. C. "The Decline of Theft and Violence in Victorian and Edwardian England." Crime and the Law: The Social History of Crime in Western Europe since 1500. Eds. V. A. C. Gatrell, B. Lenman and G. Parker. Europa, 1980. 238–337.

Godfrey, B. Crime in England 1880-1945: The Rough, the Policed, and the Incarcerated. Routledge, 2014.

Gray, D. Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Meier, W. Property Crime in London, 1850–Present. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Shoemaker, R., and T. Hitchcock. London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of a Modern City, 1690-1800. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Author Credits

This entry was written by Barry Godfrey, with additional contributions by other members of the Digital Panopticon project team.